CARLOS MOTTA

THE DREAMERS (working title)

—in progress, expected completion 2019-2020

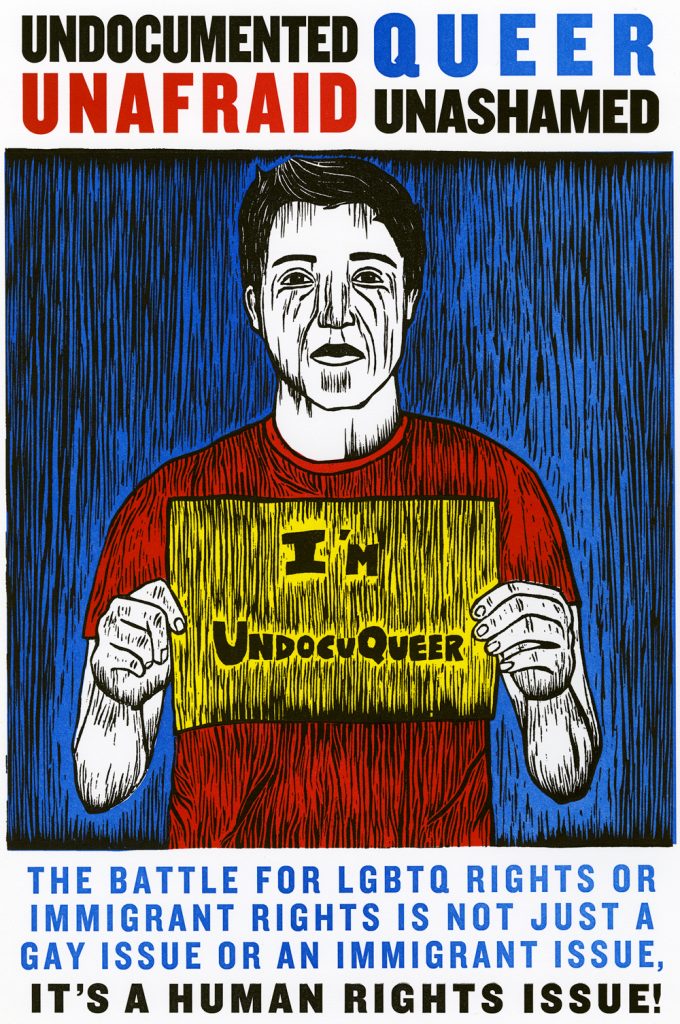

Felipe Baeza (2012): ‘Undocumented, Unafraid, Queer, Unashamed’, digital image. © Felipe Baeza.

THE DREAMERS: SYNOPSIS

The Dreamers (working title) will be video installation featuring three video portraits of young undocumented immigrants in the United States—known as Dreamers—who are seeking a path to citizenship, and series of complementary discursive community events that engage the social, cultural, and political challenges faced these communities in present day America. The project focuses on the lives and activist work of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex (LGBTQI) Dreamers to show how sexuality and gender, along with ethnicity, race and economic background, are intersectional issues that define the environment of marginalization and discrimination that immigrant youth are subjected to. The project seeks to contest the mainstream media narratives around immigration and sexuality by presenting the nuanced real-life narratives of living in the United States at the margins of the legal system as immigrants and sexually/gender diverse individuals.

ARTIST’S TOPICS AND BACKGROUND

I am an interdisciplinary artist working primarily with video, photography, installation, sculpture, and discursive events. My work draws upon political history in an attempt to create counter narratives that recognize suppressed histories, communities, and identities. I engage with histories of queer culture and activism to insist that the politics of sex and gender represent an opportunity to articulate definite positions against social and political injustice.

Since 2005, I have been working on the Democracy Cycle, a series of installations, online projects, and video works that focus on the challenges and limits of democracy in society from a variety of marginalized perspectives: The Good Life (U.S. interventions in Latin America and street perceptions of democracy as a form of government from Mexico City to Buenos Aires, 2008); Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice (assassination of left-wing and liberal political leaders in Colombia, 2011); Deus Pobre (the history of liberation theology in the Americas); We Who Feel Differently (histories of international LGBTIQ activism from the 1960s to the present, 2012); Gender Talents (grass roots trans and intersex movements internationally, 2015); Patriots, Citizens, Lovers (LGBTIQ movements in Ukraine in light of Russian intervention, 2015); and The Crossing (middle eastern LGBTIQ refugees seeking asylum in Holland, 2017).

The Dreamers focuses on the challenges faced by undocumented immigrant youth in the U.S. since the reversal by the Trump administration of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), to give them a path to citizenship. The project focuses on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex and Queer (LGBTIQ) Dreamers— and in particular to grass roots social activists who foreground the intersections between sexual orientation/gender identity and immigration law. Among the issues at stake is the deportation to countries where the expression of their sex and gender could represent a threat to their lives.

Like the other projects in the Democracy Cycle, this work will be anchored in a documentary approach using interviews, video portraits, and discursive events to expose issues of subjectivity in relation to these political challenges. I am interested in exposing the psychosocial effects of these conservative political moves on the Dreamers (and U.S. society at large) while exposing racism, classism, homo and transphobia, and sexism as structural issues in the U.S.

CONTEXT: DEFERRED ACTION FOR CHILDHOOD ARRIVALS (DACA) AND THE DREAMERS

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigrations Services’ website the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is: “On June 15, 2012, the Secretary of Homeland Security announced that certain people who came to the United States as children (known as “Dreamers”) and meet several guidelines may request consideration of deferred action for a period of two years, subject to renewal. They are also eligible for work authorization. Deferred action is a use of prosecutorial discretion to defer removal action against an individual for a certain period of time. Deferred action does not provide lawful status.”

Donald Trump ended DACA, which was set up by President Barack Obama, in September 2017, with a six-month delay to encourage Congress to pass the legal protections into law. While Trump has since proposed an immigration deal he has recently insisted any deal to protect undocumented immigrants shielded by DACA, should include broader reforms to the immigration system. He wants to limit immigrants’ ability to sponsor family members and end the diversity visa “lottery” system. Today, DACA’s future seems uncertain.

This uncertainty is devastating for Dreamers whose lives are negatively determined by the lack of rights granted to legal immigrants in the U.S. For these young migrants the U.S. is their home country and often don’t have ties in their families’ countries of origin. The fear of deportation and of being stripped of their lives in the U.S. is a major hindrance to their personal and social development.

LGBTQI Dreamers face additional fears. In many instances being deported to their families’ countries of origin could represent devastating consequences, as serious as death. This fact has been documented by the reports of at least on gay man, Nelson Avila López, who was deported to Honduras, where he was incarcerated after being confused by a gang member, and later died in a prison fire (New Yorker, When Deportation is a Death Sentence, 2018).

According to global collaborative platform wikigender.org: “The intersection of LGBTQI and undocumented identities manifests not only in social discrimination, there are additionally systematic disparities at the policy level as well. Before the recent federal repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), same-sex couples were barred access from benefits allotted to heterosexual couples. Although the repeal of this act has positive implications for the rights of bi-national same-sex couples, the statewide limitations on same-sex marriage still act as barriers to many committed same-sex partners, unable to marry in their own state. Thus, for same-sex bi-national couples, both marriage and immigration reforms need to occur in order ensure the equal provision of rights to both same-sex and different-sex couples. One such reform would occur by passing the Uniting American Families Act, opening family-based immigration sponsorship to committed same-sex partners, even without an official marriage license. Similarly, asylum and detention standards disproportionately affect LGBT individuals; the one-year limitation to file an asylum claim can be more difficult for LGBT individuals navigating social stigmas and the “coming out” process. In detention, LGBT individuals have little support or space to report cases of sexual violence. Although there are no official policies on how or where to place transgender individuals in detention, many are placed in solitary confinement as a “safeguard” against the “physical and sexual abuse by other detainees when [they are] placed with the general population because of their physical appearance.”

Through my proposed project The Dreamers intend to produce significant materials and knowledge—beyond what circulates in the mainstream news cycles—about queer immigrants and their social, political, and cultural concerns, in order to increase their visibility nationally and internationally. The project attempts to become a resource to learn about the precarious conditions of migrant sexual and gender minority communities and their encounters with draconian U.S. immigration laws.

TARGET AUDIENCE AND METHODOLOGY

The main target audience of the work will be the Dreamers themselves along with other communities of undocumented migrants. I perceive a tremendous lack of exposure that focuses on issues of subjectivity, real-life stories, and how top-down politics overtly determine the lives of young LGBTQI migrants. With this in mind, the project intends to be useful for the activists featured in it: to advance their cause, to serve as a document of their work, and to respectfully, responsibly, and collaboratively represent their ideas.

I also intend to engage various immigrant communities that are divided by specific political and social interests and hierarchical relations to engage them in the value of intersectional thinking and building coalitions of solidarity. I will access these communities through interpersonal networks. The Dreamers will expose a meta-conversation that is largely unknown to the general public to impact the perception of these issues by producing discourse presenting it at mainstream cultural institutions with diverse audiences and publics.

I think there is a need for art projects that engage directly with social and political realities in thorough and direct ways that aren’t merely referential, circumstantial, or aestheticizing. I am interested in art projects that show long-term investment in research and aesthetic questions, and that are a vehicle for communication and social transformation. I believe in art as a methodology and as a practice, but not that much in the static life of the art object, and the seemingly undisputed autonomy it is claimed by many to have.

The methodology for my work is influenced by Latin American documentary film from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. These decades staged several forms of resistance to what these filmmakers termed “American imperialism and bourgeois neo-colonialism,” and witnessed the production of alternative ways of social empowerment via the politicization of culture. Filmmakers such as Fernando Birri and Fernando “Pino” Solanas in Argentina; Carlos Alvarez, and Jorge Silva and Marta Rodríguez in Colombia; Patricio Guzmán in Chile; and Jorge Sanjinez in Bolivia used film as a political tool to inform, instruct, educate, and stir “popular” audiences about their social conditions, and their political needs, rights, and responsibilities.

A shared interest for all of them—and a central subject for my projects in the Democracy Cycle—was the production of alternative ways to construct “public opinion.” A critical position with regard to the largely unquestioned manipulation of the mainstream media’s production of political and social consent was essential to the creation on new forms of mediatic interaction. Influenced by cinéma vérité in France led by Jean Rouch, and its informal aesthetics, some of these Latin American filmmakers where also going out on the streets equipped with a microphone and a hand held camera confronting pedestrians with difficult questions, documenting social movements, and talking with individuals and groups about politics and society.

These historical precedents, as well as my growing concern about the corporate structure of the media—and its biased reporting in the name of the public—led me to use the interview form in in the different project of the Democracy Cycle and now in The Dreamers. It was soon clear to me though, that I wouldn’t make films but use only the interview form to underline and contest its potential for the acquisition of knowledge and information. While interviewing is commonly only one of the features of a documentary film, the interview for me is the means and the end.

I intend to focus The Dreamers on the work and the lives of three activists and develop a documentation approach (based on extended interviews) in collaboration with each one of them. This would range from short video portraits to performative reenactments (depending on the activists’ interests and how THEY would like to represent themselves and their work). Initially, I envision this work as a three-channel video installation that would also be a stage for social—awareness-raising—events developed for the local community.

IMPACT AND PRACTICE

Over the past decade I have developed an ethical working method to provide alternative histories that are more inclusive. I have been fortunate to have produced and presented my work around the world, working with different communities and subjects, engaging with a myriad of political issues, and exhibiting in all kind of art spaces. My work has gained success because of it commitment to the communities it represents, for its attempt to develop a collaborative practice of self-representation, for being knowledgeable of its historical precedents, and for its experimental character in terms of artistic strategies and form.

Over the years the work has been a catalyst for conversation amongst different groups in-and-outside the art world. Artists, art professionals, and community activists often reference my projects, and there has been a substantial amount of media coverage about the different works beyond artistic publications, which have at times led to considerable debates about the issues at stake.

A relevant example of the reach of the work is my recent project The Crossing, commissioned by the Stedelijk Museum in 2017, where I worked with eleven Middle Eastern refugees in a series of video portraits that express their experiences leaving their home countries due to of homo and transphobia and their encounters with the immigration system in The Netherlands. Thousands of people attended the exhibition, there were often lines to watch the videos, and there have requests to screen the videos in the Spanish parliament and the United Nations refugee office.

Another relevant example is the symposium Gender Talents: A Special Address, developed in collaboration with Electra and Tate Modern in London in 2013, where we convened a dozen high profile gender theorists, including Paul Preciado and Jack Halberstam, to discuss the gender binary and alternative ways to experience and perform gender in society. The event was attended by more than one thousand people and continues to be referenced as an important contribution to such discussion.

My work has challenged political histories in an attempt to construct discourses of opposition to social injustice through artistic, documentary, historical, and critical reflections. With The Dreamers however, I am shifting my focus and involvement toward issues of sexual difference and migration, a topic that is deeply personal, yet I have only tangentially addressed in my work (I am a Colombian queer immigrant living in the U.S. for twenty-one years). This project is rooted in a personal and political commitment: The work will shape itself as an activist and informational tool and it is a project where empathy and personal experience are its foundational motivations.

My work is at a pivotal turning point, which I will embrace with The Dreamers. My artistic voice and political positions are becoming particularly poignant; I will make use of this to ask urgent questions about the historical oppression of migrants in the U.S.

STAGE OF THE PROJECT

The Dreamers is at its beginning stages, it is being scripted and conceptualized. Yet I Have received confirmation by Ben Rodriguez-Cubeñas, Director at the Rockefeller Brothers Fund Culpeper Arts and Culture Program that they will provide funds in the form of a grant for the entire production of the project.

I have also secured its public presentation by three prominent U.S.-based cultural institutions: Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Boston; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA); and Portland Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA), which will provide funds to produce its institutional presentation and produce the discursive events components, at each venue respectively, and will also show the work in group exhibitions (ICA and SFMoMA, 2019) and a solo presentation (PICA, 2020), along with and a series of events (workshops, panels, performances and other discursive outputs).