by Carlos Motta

Presentation for the symposium “Digital Art & Democracy: People, Places, Participation” organized by Jennifer Gonzalez, Associate Professor, History of Art and Visual Culture, UCSC—June 1, 2012

Download PDF here.

DEMOCRACY

The word “Democracy” is often used indiscriminately by anyone looking to represent her or his own personal or collective interests.

“Democracy” comes from the Greek demokratia or “popular government”: from demos or “common people” and kratos “rule, strength.” History however has shown how the ruling elite has controlled the exercise of the government and frequently excluded “the common people” from decision making processes, and especially “the common people” that differ from them in their racial, ethnic, religious, sexual, or gender backgrounds, or simply think, feel or act differently from established social, ideological or political norms. The common belief in democracy as an inclusive form of government—political but also social and inter-personal—confronted with the reality that people around the world, face vis á vis the exercise of power, begs for the articulation of a systemic critique that dematerializes democracy’s “potential” from its actual “implementation” from every angle where representation and power intersect.

Art is fundamentally an act of representation: As such its politics transcend a meta-conversation about itself or its form and situate it at the center of the power struggle. Who is speaking? Who is being addressed? Who or what is being talked about? What strategies are being employed to construct that discourse? The “politics of representation” have been at the center of artistic discourses since the early 20th century, but most strongly since the 1970s—coinciding with the feminist and sexual revolutions, the civil rights movements, and other social movements. Art has been used to question power and the perverse ways in which it manifests itself in society, but primarily to point to the ways in which power determines, oppresses and shapes people’s lives. Art however isn’t exempt from reproducing those very things that it sets out to critique. The “Institution” of Art is intimately complicit with the exploitative capitalist drive and its very existence is related to the financial and cultural systems that produce forms of discrimination and exclusion.

Through my art projects I have been primarily investigating the three ideas I presented above: How do democracy’s promises reflect the perspective of marginal groups that exist outside the reach of legislative democracy? How can Art be used as a way to question the structure of power, to think about artistic platforms that engage democracy as a subject matter and to propose alternative sites for democratic exchange? And, what is democracy?

Back in 2005 I began a cycle of works, which were eventually grouped under the title “Democracy Cycle.” These works approach these questions regarding democracy from different perspectives: foreign policy and intervention in the project “The Good Life,” political exile and cultural assimilation in “The Immigrants Files: Democracy Is Not Dead; It Just Smells Funny,” political and ideological genocide in “Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice,” religious faith as a form of social liberation in “Deus Pobre: Modern Sermons of Communal Lament,” and the systematic discrimination of diverse sexual and gender expressions in “We Who Feel Differently.” I intend to briefly discuss aspects of two of these projects today in an attempt to exemplify the way I have approached the relationship between politics and representation or more precisely the limits of democracy regarding the politics of representation.

I will now show an excerpt from “Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice.” In 2010 we had presidential elections in Colombia. In my opinion, these elections were definitive, since they represented an opportunity vote out the legacy of a widely supported and celebrated right-wing president, Alvaro Uribe Vélez, who held power for eight years and whose politics, in short, were based on militaristic confrontation and capitalist expansion. The electoral campaign season was thus an opportunity to recall the systematic elimination, of the Left: Progressive and moderate liberal politicians that ran for presidency in the last one hundred years. The Left has been violently silenced by the enemies of socially responsible ideologies.

For “Six Acts” I invited six actors to read in public squares throughout Bogotá, historical speeches originally delivered by six presidential candidates that were killed while campaigning in elections since 1903. All speeches underline the necessity to think of peace as the primary achievement of Colombian politics. “Six Acts” intended to re-insert these forcefully silenced ideas back into public circulation as a way to sparking a conversation about these seemingly “forgotten” lessons of our recent history. “Six Acts” wanted to propose a narrative or aesthetic justice in a place where legislative justice has failed to deliver.

I will show two clips from “Six Acts”: “Act III,” where actress Ivonne Rodríguez performs a very short speech from 1986 by Communist leader Jaime Pardo Leal, and the “Epilogue” to “ACT IV,” which shows the interaction Atala Bernal—another actress who performed a 1989 speech by liberal leader Luis Carlos Galán—had with the public that observed her reading on the square. I believe these clips will be productive within the context of this symposium since we are interested in discussing the democratic potential of artistic and discursive sites.

Needless to say, this interaction was incredibly challenging for all of us on many levels: What happened when the space of artistic representation was viscerally confronted to everyday politics, when fiction and truth collided? What ethical problems were triggered by this public intervention? How were class relations made evident by this interaction? What constitutes the event as a democratic platform: the performance itself or its documentation? How does this happening exercise reflect the “political efficacy” of art?

The group of elderly protestors obviously “believed” the actress’ words, despite the fact that they had been spoken in 1989. Her performance and the socio-political context of present day Colombian politics made these words resonate as immediate and urgent. What was conceived by us (the actors and I) as a symbolic gesture was read as literal and as factual. Our attempt to question the potential to symbolically produce a democratic exchange became a democratic exchange in itself beyond our expectations. But we could not “deliver” what the speech promised, and the elderly protesters could not help but be disappointed (again!) by our “deceit.” But did we really “trick” them? Did this artistic platform “fail” or did it indeed succeed in creating a conversation about the limits of power? How does this act represent all subjects involved?

I am often bothered by what political art’s critics call the “inefficacy” of political art; its inability to change people’s social realities directly as a consequence of its aesthetic or conceptual impact. The critics often underestimate the actual political potential of an “encounter.” The “efficacy” of this action, whether or not it was intended, laid precisely on the activation of the site of conflict and in colliding the “symbolic gesture” with the “precarious social needs,” thus potentially creating a democratic platform of exchange.

Ethically, this event made evident the socio-political relations that are at work in Colombia every day: Class relations of (lack of) access and privilege. The production of art and intellectual discourse are a luxury in a context where basic needs—such as hunger or shelter—are people’s immediate necessities and priorities. We, artists, actors, have made ourselves belong to a class with access to abstract reasoning, even if we may intend to use this privilege to produce counter knowledge of to question power. But how implicated are we already in reproducing oppression and exclusion with our initiatives? Is the “democratic platform of exchange” I mentioned above perhaps not that “democratic” after all? I believe as producers of culture we must be very careful not to reproduce forms of alienation and exclusion based on what our intellectual or liberal agendas might dictate as politically correct or artistically progressive. At the same time as artists we must let the Sign to do its work. Perhaps our task, as cultural makers is to recognize the complexities at work in the tactical juxtaposition of social realities and artistic gestures in order to don’t loose our critical perspective.

To conclude this section I want to address what I think are the two most important aspects inherent to a public intervention that may call for audience participation: The performance itself and its subsequent life as a document. The act itself produced a document, which is what, in this particular case, right now, we are discussing as an artwork. How do these two points of access to the work reflect issues of democracy and access? I believe the work has several lives: The work was in time and space a temporal intervention, a performative gesture, a symbolic sign. The work is now a document that represents the original event and has to be approached as another kind of platform with its separate set of concerns. How can these two aspects of a work be thought of as democratic spaces? Is direct access to the act proper more “democratic” than its reception as a document?

In “Six Acts” —the document— democratic space is more, let’s say, traditional; it is dictated by forms of access to art, which refer back to institutional politics of outreach, such as the University or Museum for example, which may present it. The “democracy” of the work in sense lies in its speaking to an audience passively and enduring the violent re-contextualization that institutional frameworks impose onto it. The work must resist the models of racial and gender exclusion, for example, produced by hegemonic institutions.

There are other forms of generating democratic spaces that resist these models for the dissemination and presentation of art. The Internet is one of such forms—its growing access permits the formation of one’s own spaces for the production, presentation, and dissemination of projects that exist beyond conventional ways of “legitimation.” The vastness and proliferation of online spaces is evident today: People are creating their own media channels, news outlets, opinion blogs, artworks, festivals, etc.

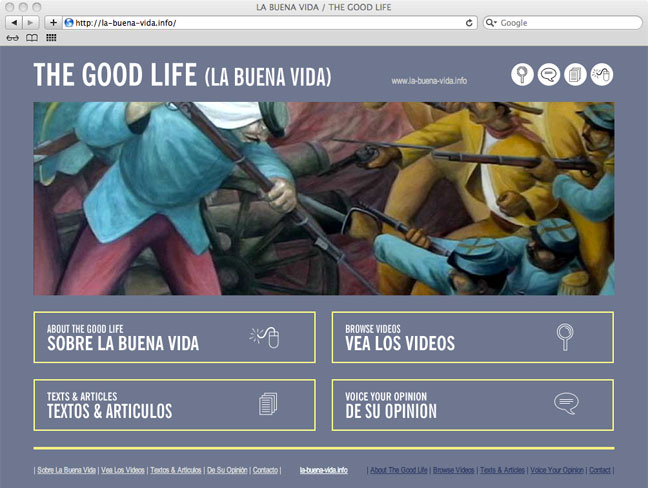

Back in 2005 I began a four-year journey throughout Latin America, visiting twelve cities with the intention of generating an online archive of video interviews with pedestrians, who would address the local perception of democracy as a form of government. The resultant work is titled “The Good Life.” This online project presents over 500 interviews with women and men from all paths of life, social backgrounds and ethnicities that responded to a questionnaire that sought to investigate the way folks think of democracy and how within the context of Latin America there’s a profound relationship between the idea of democracy and U.S. foreign policy in the region. I wanted to produce such an archive based on my dissatisfaction with the dominant political narrative represented by the corporate media, which had always presented democracy to me as the only thinkable form of government, yet which failed to problematize its origin in the region: Democracy in Latin America is tied to violence and exclusion in ways that defy democracy’s very etymological definition; its imposition has been as tyrannical as the very military rules that proceeded it and it intended to counteract.

“The Good Life” was also conceived in response to a history of Latin American conceptual artworks since the late 1950s—primarily filmic and performative—that intended to use conceptual art’s strategies as a means of producing gestures with political intent. Street theater, ephemeral interventions, durational performances in public space, endurance art, etc. were forms of resisting military oppression, politically motivated forced disappearances, ethnic genocide, the forces of masculinism, etc.

I would dare to suggest that these forms of resistance are predominantly consolidated today as online expressions: blogs, websites, and social media. The Internet has provided “dissenters” throughout the world as space to write their own histories and perspectives and to directly speak to their intended audiences. Take for example “Generación Y,” the widely known blog by Cuban opposition journalist Yoani Sánchez, where she reports aspects of Cuban politics and life, which the official government deems as oppositional propaganda. “Generación Y” is an alternative news source and an outlet for counter information.

Or alternatively, think of the wide use of social media channels to organize political action and protests throughout the world. These platforms, political, artistic or otherwise, represent a shift in the representation of subjects. The aspect of that shift that interests me the most is the potential for self-determination, self-presentation and self-contextualization as truly democratic strategies.

Self-representation is, in my opinion, the key aspect when thinking of the radical potential of artistic practice today: The politics of representation could be perceived as having opened to a structural reconfiguration. This is a positive shift in the sense that a wider network of channels is available to encounter “other” forms of, for example, journalism or artistic production.

My experience making and living with “The Good Life,” is that acting upon one’s own desire to see change occur, namely making one’s own institutions and creating one’s own narratives, shifts the narrowly defined institutional limits of democratic exchange: Democracy is not a gift but a given, one doesn’t receive but one produces. One becomes an agent of change. These ideas point to access as a form of liberation: Access to knowledge, access to education, access to like-minded individuals or communities, access to the public recognition of historical forms of alienation.

It would be naïve to think that power relations don’t exist within the realm of online connectivity and production, but these spaces have enabled a myriad of alternative forms of production to emerge proliferating social and artistic histories and de-centering the cannon, or at least making it less of an oppressive and unbending narrative.