Interview with Karim Ainouz

by Allen Frame

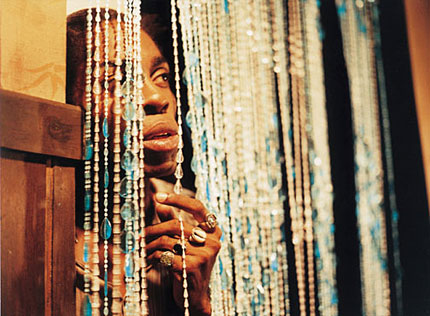

Madame Sata, the first feature film by Brazilian director Karim Ainouz, is a sizzling portrait of Joao Francisco, (played by Lazaro Ramos) a paradoxical, real-life character from the 1930's bohemian underworld of Rio. The film follows him in his various guises, as street tough, as hustler turning tricks, as passionate lover, as loyal friend, as prisoner, and finally, as the fantastic Madame Sata, legendary drag performer. As Stephen Holden writes in The New York Times, Madame Sata "is a voluptuous, hot-blooded portrait of a social outcast, a black, homosexual criminal who in acting out his gaudiest Hollywood dreams, transcendently reinvented himself."Allen Frame: Are you optimistic about the current success of Latin American cinema?

Karim Ainouz: Totally. There IS something happening in Latin America. Definitely in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile (but not as much,) Cuba, (but not that much for various reasons.) I think there's an outburst — maybe that's a little bit too much to say — but an outburst of new auteurs in Latin America. Now there's a film like El Crimen del Padre Amaro from Mexico, and there's Japón. There's a film like 9 Queens from Argentina but also a film called La Ciénaga. There's some diversity and it's very healthy. It exists in the U.S., it exists in Europe, why can't it exist in Latin America? I don't have to make a film like El Crimen del Padre Amaro. Somebody's going to do it. That's very liberating. I don't feel like I have to make a mainstream Brazilian film anymore.

film still from Madame Sata

AF: La Ciénaga is such an affecting story of a family's dysfunctional inter-relatedness.

KA: It's one of my favorite films, unbelievable. I think the scene in Argentina is the most exciting in the world of cinema today, for two reasons, - because Buenos Aires is the city with the most film students per capita, so there's clearly a forum for critical debate and discussion. Then, it's a city that has really great film critics... If you see a film like El Bonaerense, or Tan de Repente, or La Ciénaga, there's a freshness. Not freshness, because that's what you had in indie cinema here (the U.S.) in the early 90's. There's a sophistication there. But you find examples of that in other countries, in Mexico, in Brazil. I think there will be much more interesting films in Brazil this year than last year.

Things are changing in different ways. It's a generational thing, but a generational thing that's trying to find a voice, and when you're trying to find a voice in Latin American cinema, it's about improvising. It's about diversity and experimentation. People are doing things with narrative but twisting things around. You can identify Taiwanese cinema or Iranian cinema very clearly, but what's interesting about Latin American cinema is that it's very mixed.

It's a very special moment. When you think of last year, again Tan de Repente, El Bonaerense, Japón, El Oso Rojo, Y Tu Mama También – there's a movement that's happening. As a Brazilian I always felt like I was on the World Music list. Now I feel like I'm on the Pop charts. And that's great. I don't feel like I have this "ethnic" identity. La Ciénaga is not a Third World film. It's a very local film but one anyone can see and relate to.

What I've been thinking about Brazilian cinema, though, is that it's shameless. When I say "shameless," there's this look at everyday life, an unapologetic look at what's happening in front of us and that going into a kind of poetic register. It's so beautiful. Especially in Argentina, there's this poetics of daily life. I think that's going to happen in Brazilian cinema next year. I have a couple of friends who are doing films, and I know they're going to be something like that. The problem with Brazilian cinema up to now is that there are very few film schools. I'm not saying you have to have film schools to have good films, but everybody kind of went into advertising because there was no way to make a living if you were doing film. There's a whole generation of people who are doing amazing work, but it's very much informed by advertising and a fast pace. There's no information about what it's like to be in the world.

In Argentina, too, in that culture, you have collaborations. There's not a lot of money but people help each other. It's a different kind of mindset. When you're trained in advertising, your crew is going to want to be well paid. They want to do a professional job and all that and that doesn't leave much room for invention, as it does in places like Mexico. Mexico produces 14, 15 films a year. It's nothing. You have to improvise to get that. Did you see the film 1000 Clouds in the Sky? It's not great, but it's really inventive, really interesting, and done with very little money.

AF: Is the collaboration for you with the Director of Photography important?

KA: In my case, I have a trio that I work with really closely. My DP, my production designer, and the person who helped with casting. (Walter Cavalho, Marcos Pedroso, and Luiz Henrique Nogueira, respectively.) I don't even know how to name his work. He's somebody who helped me find the actors, prepare the actors, take care of the actors, rehearse the actors and really made a point of their working together. How you bring an actor to the set, and how the actor is treated on the set, and all of that makes a difference when you have a camera that's "licking" your actors. For instance, this famous "love scene" in the film. The camera is literally licking the body.

film still from Madame Sata

AF: I understand the film was very controversial. Because of the lovemaking scene between two men?

KA: When the film played Cannes a lot of the headlines in Brazil were about that scene.

AF: Because it was a sex scene between two men, or because both men were masculine, and the man on top was black and the man on bottom was white?

KA: It's a combination of things. When it came out six months later after Cannes, that scene was way less the topic of discussion, but it was still there. Clearly, I was not at every screening of the film, but people were shocked. Two or three people would always walk out. My reading of that is that it is not a classic love scene; it's a portrait of intimacy between two people. Then, it's about two very masculine men having sex and it's not about penetration. I think when people think of men having sex, they think about penetration. There is that in the film, but there's a lot of foreplay, there's penetration, there's a lot of after play. So that, too, is unsettling. There is no soundtrack in that scene. The sound is the noise of the body. There's sweat. There's no desire to make it glamorous or clean. In one way, it's too close to home. It's like watching somebody having sex in front of you. And, of course, the controversial reaction is about homophobia, too.

Brazil is a very macho country. I have this friend who went to the film with his girlfriend, and he said he was really disturbed by that film, and I said, "What's the problem?" and he said, "Those guys are way more masculine than I am. And I was there sitting with my girlfriend." So I think it's a combination of things that make that scene controversial. I think it's about homophobia but also about a fear of intimacy that people have.

film still from Madame Sata

AF: There are a lot of hand-held shots in the film. How improvisatory is your method?

KA: I can't just get a camera and do a film. I do work from a concept and that concept gets more sophisticated and complicated. It is very fluid. It's almost as if I built a bed for us to be able to inhabit, metaphorically speaking. So the bed is super-constructed. It was very clear to me what the film should look like, what kind of texture it should have, what kind of depth of field, and what kind of method with the actors. The sound was something that became clear as I went along, that I discovered as I was editing the film. The production designer was super clear. It was about shooting existing places, and it was about rearranging those places for the period of the film. We knew what colors we wanted to use. It was all discussed thoroughly. But then what that construction allowed me to do was to be able to improvise with a big safety net.

The first day of shooting, when Renatinho goes to visit Joao Francisco in this kind of dungeon place, I didn't really follow the storyboard, and that was a revelation to me. The actors couldn't keep their marks because they hadn't shot a film before, and I had shot the rehearsal on tape so I knew where I wanted the camera to be, but I just let the DP kind of move around. So it was a very messy day because every take was very different. And I thought, God, I've spent years constructing this, and now all of a sudden it's slipping away from me. What's happening? I was quite moved with what I was seeing in the video, but at the same time I was feeling like I was losing control. And the second day of shooting was a scene that is not even in the film, which was totally choreographed, where the camera is here, and it goes to there, the character moves from this place to that place. When I compared the footage from the two days and the two ways of shooting, I was way more moved by what I shot in the first day. So I kept on experimenting like that.

And I remember the other thing that was very moving was that we were editing the scene during the shoot and my editor did a jump cut and I looked at it and said, "This is what we need, we need a formula. Some things have to be shot in continuity, and some have to be shot out of continuity." It was a film that took years to be made so there was a lot of planning. It was a way that I kept the project alive with me-- to plan and plan and plan, to know the lens, the setup, and when the project happened, I was discovering the pleasure of improvisation. It was improvisation that was informed by months of preparation, years of thinking. I shot a lot of the scenes on tape because we rehearsed on location a lot, so I had my video camera and I was sketching. That allowed me to discover the space of the scene for the actors. Then it's a construction that's way more organic than just deciding it's a dolly shot from here to here.

I shot on 35. I wanted to shoot on 16 but I couldn't. There was a contract saying I had to shoot on 35. I think the 16 would have been so much more appropriate to this kind of working method.

I was very lucky to have the DP that I had. Walter Carvalho. He's somebody who'd done loads of films and has done both traditional and less traditional types of cinematography but someone who's willing to experiment. He has his reputation already, and he's willing to go places and experiment with things. We did a lot of tests to decide on the process of bleach bypass that we used. The blacks are deeper and the colors are more saturated. We did a 100 per cent bleach bypass on the negative. People usually do it on the print, but we did it on the neg. It's daring. You don't have that much chemical control.

AF: Yes, he was willing to lose so much information in certain dark scenes. I remember in one scene Taboo is coming down the stairs and you cant make out any of his features until he passes through one ray of light and tosses his head back laughing and it is so effective, so punchy, to have that slender moment of illumination. And to suggest the rest that you don't see. I love the effect on the women's skin, too, on the cabaret singer, for instance, who looks like someone in a Madame Yevonde photo from the 30's, or out of Brassai's Paris of the 30's.

KA: Yes Brassai was a big inspiration. That process with white people makes them look whiter; it looks more like period makeup.

AF: The older actors in supporting roles in your film are very interesting, too.

KA: The reason I worked with Renata Sorrah in my film is that she did an amazing film in the late 60's, 30 years ago. She only did TV after that and she has never done a film since then. It's like shooting on location, working with older actors. There's so much they bring with them.

film still from Madame Sata

AF: I just watched the DVD of Fassbinder's Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, and the interview with the older actress Brigitte Mira is fascinating.

KA: It's my favorite film of all time. I just bought the DVD. She is amazing. I think that, in a way, to work with Marcelia Cartaxo, who played Laurita, was a bit like that. In her case, it was a bit perverse of me. She was the main actress in a beautiful Brazilian film of the early 80's, Hour of the Star, for which she won a Golden Bear in Berlin in '83, and she's been playing that role ever since. That role was very down, depressed, ugly. In my film I wanted her to be very solar.

The reason I chose the actor Emiliano Queiroz who plays the bar owner, Amador, was because he came from the same city I come from, which is kind of far away in the North, north of Recife. Maybe he would bring something familiar to me. He did a movie, in 1968, a play with this kind of damned Brazilian theater director. He played a kind of big queen who's addicted to pot and lived with this prostitute, and I wanted to get that guy to play something completely different but with that information, somebody who knew that universe.

AF: And the actors playing Joao Francisco (Madame Sata) and Taboo are from theater?

KA: Flavio Bauraqui (Taboo), it's his first film. Felipe Marques (Renatinho), it's his first film. Lazaro Ramos (Joao Francisco) is a theater actor. He's done two films before mine, small parts. They all live in Rio but Lazaro is from Bahia. Taboo is from the South of Brazil, and Felipe is from Rio.

AF: What's next?

KA: I'm doing an installation and I'm writing another film.

AF: About?

KA: I can't really say because I don't have the rights yet, but I'll tell you the universe of the film. It takes place in the region where I come from in the northeast, the backlands of Brazil. It's the story of this young girl, who's 19, and she wants to leave to go to the big city. It's really about desire and how much you go into your desire and how much you surrender, but it's really also about hope and what it is to be somebody that age in Brazil. It's based on a real-life event. She does something radical to be able to get out of there. So it's a character study, a film about the woman who runs away. It's exterior. There's a lot of daylight stuff. It's a very solar film. And I will be able to play more because it's contemporary, and there's a constellation around her, but the film is a kind of portrait of her.

AF: And what about the installation?

KA: I like to do portraits in time, and doing an installation is great because it's really a visual experiment and there are no boundaries. If you want to tell a story you can. If you don't, you don't. It's really about space, sound, and motion, which is the essence of cinema at the end of the day. One thing I like about it is the possibility to experiment as you do with experimental filmmaking. I had this small 16 mm camera and I just shot people dancing at Carnival, common people, people who were drunk, people who were not drunk, young people, and they do become characters, so when I do something like that, I'm more interested in time, perhaps the permanence of time and space, specific to this Carnival thing, how can you explore it physically instead of through your gaze. And it's such a privilege that I go there every year, and I want to share that experience with other people, but how do you do that? Through atmosphere, through image? I'm trying to figure that out. I'm interested in the idea of character and the idea of the human experience much more than I'm interested in the idea of telling stories...

© Allen Frame-Karim Ainouz 2003

all images © Karim Ainouz, courtesy of the artist

Allen Frame is a photographer whose book Detour, a compilation of his photographs over the last decade, was published by Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg in 2001. He teaches photography in New York and will be the curator of an exhibition of photography and video at Art in General in New York in 2004 called "In This Place."