Interview with Alex Morel

by Susan De Seyn

Twenty PhotographsSusan De Seyn: Someone we both know once said that when you are talking about photographers that take pictures of people, there are two types, “Those who photograph people they know and those that photograph strangers.”

Your titles are familiar. You get close and keep cool. Even if I didn’t know, I would know you knew. You leave clues.

How far along did you get in photography before you discovered that you were a photographer best suited for intimacy or was that your tack from the get go?

Alex Morel: Around ’94, ’95, I was a full time student at ICP. I was working on my first attempt at social documentary photography and the topic was Latin American immigrant workers. I knew I didn’t want to photograph them in a reportage type of way . . . they were difficult to access – so little by little – meeting people in the street, coming back every day, getting there early and spending the whole day…I started to get to know them. Some of the people would invite me to their homes. I got to know some of them really well – and they would show me how they lived and their family albums.

Some images started to come out that were less traditional documentary and more intimate and familiar. The “shock” effect that some documentary pictures have wasn’t there but there was a closeness… it started from there.

Binny Behind the Door, Cabarete DR, 2002.

SD: The individuals that people your photographs are all inward, intact, in thought, in and of themselves, and sometimes asleep. I mean, even the donkey seems to be thinking.

How do you “get” those images without disturbing the subjects? Or is it that you (gasp!) pose your subjects? (O.K. not the donkey).

AM: The images are not posed. And that’s some of the traces of my social documentary concern/tradition that has been left with me. Those images come to be by [my] being there and eventually being allowed to participate in very private moments. The property of feeling the present, of being aware of the present -- that's the moment I go after.

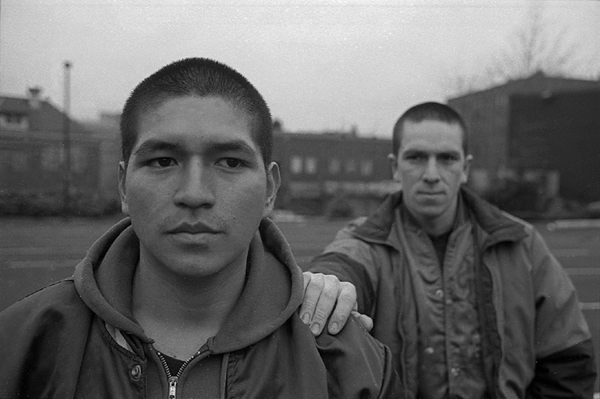

From the Latin American Illegal Workers Series: New York, 1995.

Salvadoran man at home in an apartment he shares with other friends.

SD: So would you say that you are haunting or hunting for a particular moment?

AM: …hunting sounds a bit too aggressive. I participate. I am with these people. I am not there because I want to make pictures. At the same time the pictures are not just a by-product. It’s about a trust, a balance.

Nineteen year old boy from Ecuador waiting for work early in the morning.

SD: Why is everyone so tired? And I’m only half kidding. The pacing in these twenty photographs is very slow and certainly helps emphasize the contemplative vibe. But moreover it seems like in this place - and you have brought the viewer to a place although I doubt it’s geographic - things are a bit surreal. Separately or together these pictures are less like a travelogue than what one remembers about a dream or something - which sounds a bit dramatic or romantic but …it is.

AM: The work here is somewhat slow and that might be because of those very specific moments that attract me – something happens there – something that makes me stop – I probably can’t express why literally – for me these are ideas that are probably best understood by the senses.

Natacha in Her Daughter’s Room, Santiago, DR, 2004.

SD: And you have two types of landscapes here - I’ve been thinking of them as sort of micro and macro landscapes. The micro being the clouds, the tree, the cracked ground, the pebbles on the beach - the pictures where you really get close up and isolate a subject and then flatten it out on the picture plane and the macro being Binny in the lagoon, Annika in the ocean, the car crash in the water - they really are sweeping “big” pictures, cinematic in gesture. I have to say that these images for lack of a better term - really turn me on - they just keep unwinding and unwinding - they are so generous.

What are the landscapes to you? And do you think of them as separate like I do?

AM: What you call the ‘macro’ landscapes - they serve the same functions as the more closed, intimate, interior spaces– it’s about the people’s relationship to their surroundings and how they affect one another – psychologically, physically, spatially. The word ‘relationship’ expands.

And the ‘micro’ images, well, they just started to appear within the body of work. They started talking back and saying, “I am going to stay.” For me, they are punctuation marks.

Annika Searching the Sea, Haiti, 2003.

SD: In all of these photographs there is an inside and an outside and some sort of visual discussion of how everything balances.

Can you define inside and out in reference to your photos?

AM: No, not in an easy way. I think that’s one of the issues with this work . . . perhaps, if I knew how to write better I might not be doing these images, if that makes any sense.

SD: (laughter) That’s the saddest thing I’ve ever heard.

AM: No it’s not a sad thing. It’s not a sad thing at all. Because maybe I would be ah… maybe the product of the work could be perhaps a book and that might be an interesting thing in and of itself. A kind of a book in which the narrative is not explicit, is not clear. There is narrative within each one of the images – and they all seem to carry a certain sense . . . I don’t know what the viewer really gets . . . but, for me it’s something that you feel more than you can literally understand.

La Tormenta (The Storm), Haiti, 2002

SD: So maybe it would be more accurate to say that these are not micro and macro landscapes but rather micro and macro narratives that are not linear in nature.

AM: Yes.

Dorka, Petion-Ville Haiti, 2001.

SD: What writer or book would you say that these photographs are most like?

AM: Two writers, Octavio Paz and the way he understood the present and being aware of his own time becomes really important – he does this in the way he talks about these ideas in his poetry and essays.

The other writer is Javier Marias, a Spanish writer. An interesting thing about his words and his writing is the pattern of ideas that seem to go through his head – It's his non-linear thinking that I mainly identify with.

Dry Land, DR, 2004.

SD: While there is no linear narrative in these twenty photographs there are a few details in the images that are maybe like a trail of breadcrumbs. While I don’t know where they go, I have a gut feeling that they are not coincidental.

SD: Floral patterns?

AM: There are certain ideas of patterns and flatness that I do recognize and have some attraction to. It reminds me of paintings by Matisse that I feel close to and attracted to and many others (painters).

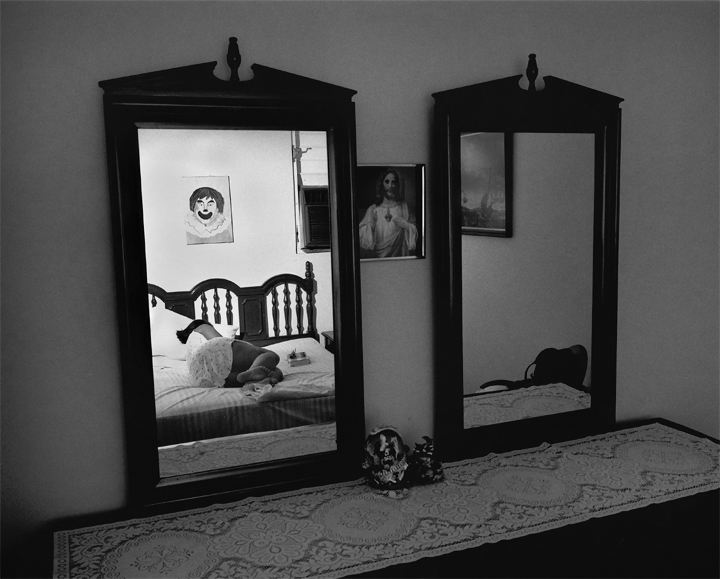

SD: Mirrors in the bedroom?

AM: Again it’s all about space and the illusion of space and a relationship of the space to the main subject.

The Clown, Jesus and Binny, Santiago DR, 2002.

SD: Haiti to New York to the Dominican and back to New York and so forth - you are all over the place.

What are the difficulties in working and producing in so many different places and how does it or does it inform your work?

AM: It’s fun and painful. It’s fun because new environments and changes really help my work, help it grow and stimulate me to produce and to react. The painful part is to not to see the work immediately. Time goes by without my seeing what I am doing. All the impressions are in my head – I do keep track of them. I know what I have. But, I may have a particular photograph in mind and I can’t see that it DID work out – so a few months could go by… So, until the time comes where I have the space where I can do all that… The traveling and the residing in different places – there are advantages and disadvantages. For example in Haiti and in the DR it is difficult to physically produce the work, the prints – developing and all that – so I have to do all that when I get back to New York.

SD: How do you decide what size an image is going to be and how it’s going to be finished?

AM: Final size is not a set thing. It has to do with whether I am showing a specific piece, the space it’s going to be in and how I want to see them finished ideally.

SD: When color, when black and white?

AM: There is no formula for that. And it’s not as simple as whatever film I have in the camera. I guess to answer specifically, it is when it works. When it works for me.

The Accident, Samana DR, 2001.

Alex Morel was born in New York in 1973, grew up in the Dominican Republic, studied at St. John's and ICP and completed his MFA at Rutgers. He divides his time between the U.S. and the Caribbean, and is currently teaching at St. John's. Among his current exhibitions is In This Place at Art in General which can be seen through January 22, 2005.

Susan De Seyn is an artist and writer. She lives and works in New York City.

Medium information: Color images are type C-prints, and the B&W are gelatin silver fiber prints. Sizes vary.

All images, Alex Morel © 1995-2004.

Text, Susan DeSeyn © 2004.