Interview with Margaret Morton

by Pradeep Dalal

Margaret Morton’s recently published book “Glass House” documents, through quiet but searing photographs and interviews, the moving story of young squatters in an abandoned factory in New York City’s Lower East Side. She explores notions of home and community among people who are living at the edges of society. Her earlier publications include “Fragile Dwelling” (2000) and “The Tunnel” (1995). She is a professor of art at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City.Pradeep Dalal: I found my way to the individuals in each of your books through their own words. The opening quote from Donny in Glass House: “I’d rather have adventures than things, because once the adventure is over, nobody can ever take it away from me,” is revealing. How did interviews become a central element in your books?

Margaret Morton: When I originally started photographing, it was in Tompkins Square Park in 1989. There was a homeless community of 150 people living in the park at a time when it was a flashpoint for the national homeless crisis. I was fascinated by the structures that people had built for themselves. That really was what started me on this project. At that time I was only taking photographs. There were people who were evicted by the police and started relocating to vacant lots along the river. I followed them and started photographing these new communities they were building. At that time they were telling me these stories that were so amazing. I came home and looked at my field notes and felt that I was not doing their stories justice. I read somewhere that you only retain 30% of what someone tells you verbally, if that. When I typed what they told me in my field notes it was my voice, the way that I write. I decided to start tape-recording the stories they were telling me anyway. So what I did since I did not have a background in taking oral histories – I was trained as an artist – I met with Kai Erikson who was the chairman of Sociology at Yale University and had done a book of interviews. I also talked to people who had worked with Studs Terkel, and I talked to Kim Hopper who was cofounder of the Coalition for the Homeless and had done a lot of oral histories. I gave myself a crash course. I did this very intensely in 1991 – two years after I started documenting photographically. From then on it became part of my work.

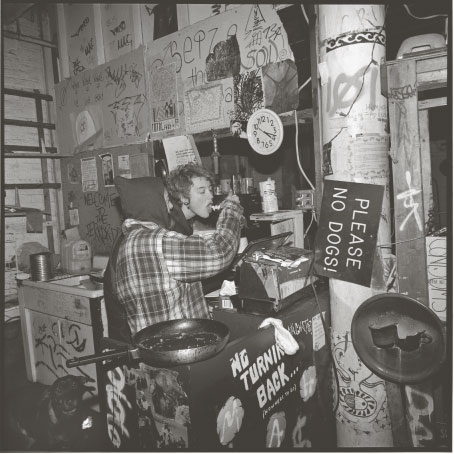

Communial-Kitchen

PD: Along with the stories of the individuals in Glass House you also gathered a lively description of their day-to-day lives: from dumpster diving to dealing with drug addiction. And the urban history of the Lower East Side is invaluable in understanding the larger forces at play. What prompted you to tell the larger story?

MM: It was important to establish why there were these abandoned buildings, because besides Glass House there are other abandoned buildings that get referred to in the text. It seemed to me that anyone outside of a New Yorker would wonder why there were all these abandoned buildings on the Lower East Side. Most people think that every apartment in every building in New York is occupied, that there is no unoccupied space. And there were all these burned-out, gutted-out buildings at that time. So I felt it was important to establish that. I have lived in this area, and have been teaching at Cooper Union since 1980, and seen all these changes, but I wanted to go into the deeper history of immigrant communities. I wanted to know for myself, not just for the reader. I do feel it important in Fragile Dwelling, and The Tunnel, and even Glass House to establish some sort of historical context. For example The Tunnel, there were people living along the tracks in the 1890s, and that's amazing. It was a very short prologue but my research was huge. I did not want to overpower the contemporary story with the history, but I wanted to simply make the point that there were these cycles: there were people living along the tracks in the 1930s during the depression, and in the 1990s it is the largest visible homeless community since the great depression. There were people living along the tracks and now they were enclosed in this tunnel, invisible to the people of the city. There was this layering of history. The Lower East Side was always a place for people to find themselves. People came from Germany or Ireland, and even in contemporary times, people from Ohio, Indiana and Michigan would hitchhike and find themselves in the East Village, in Tompkins Square Park. And it was fascinating to me that this went on from the 1840s.

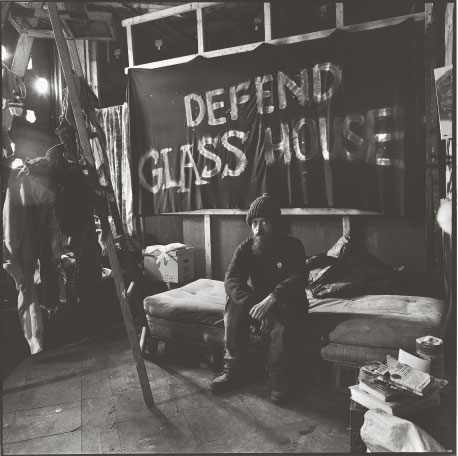

Donny

PD: Your photographs also cover several approaches: portraits, environmental portraits of rooms or spaces, details of graffiti, notices, debris, and then descriptive images of people collecting water from a hydrant or cooking, or clambering down scaffolding. There are others, such as the establishing image of the roof view with towers in Glass House and the atmospheric images in The Tunnel where the light filters down in sharp diagonals. Could you say something about the way you make photographs?

MM: When the Tompkins Square work was published and exhibited, I was taking very frontal photographs of the tents – there were a 150 homeless people living in the park and there were about 72 different structures. I was more influenced by Bernd and Hilda Becher. I took these very frontal, direct photographs that documented the structure almost as if it were a portrait. I had no people at all. I called my project “The Architecture of Despair.” So while everybody was up in arms about all these homeless people living in the park, in fact they were building their own housing. Instead of waiting for the city to come up with a solution, they very methodically, patiently and quietly went about making their own place to live. So my first project was only the architecture.

Underlying these projects is a fascination with place and place making. It was really as I got to know these people as they were relocated to other places that I started photographing them rebuilding. I do not come to this work from portraiture, I come to it from being interested in photographing architecture and places. And abandoned places. Suddenly everything just came together for me as an artist. I had this situation that I was fascinated with and could bring in my interest in architecture. The complex layered content of a situation that was occurring right now but also its relationship to the past. The idea of people making their own architecture. When I was an undergraduate I remember being fascinated by Bernard Rudofsky’s book Architecture Without Architects.

My formal interests suddenly had a life of their own, and they could feed into this much larger and more complex situation. I could feel alive as an artist. I went to Yale for my MFA and at that time it was very much about formalism. I had a strong sense of composition but at Yale nobody was talking about content. So suddenly everything started to have a deeper level of meaning for me. I could use my formalism but in a way that was more meaningful for me.

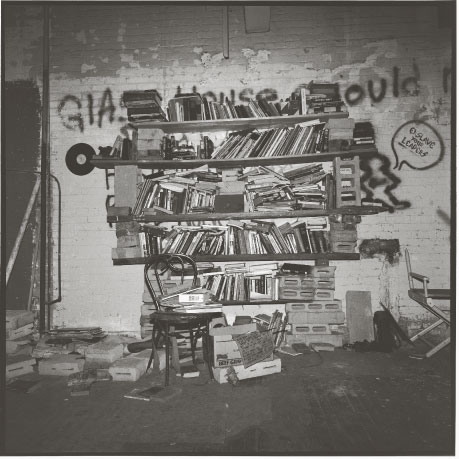

Library

PD: The places and homes in your books are put together with so little, and yet there is a lot of attention and care in their making and use that is admirable.

MM: Lots of these wooden, plywood shanties that you see in Fragile Dwelling are four-foot by eight-foot plywood, so they are very tiny, just eight feet high and four feet wide, and four walls. Sometimes they are a little larger than that. If they put the plywood sideways it may be eight by eight. It is amazing to me that on the outside it is just a plywood shack, and you would go inside and it suddenly was his home. There was a bed and it was made. The shoes would be carefully placed underneath. There might be a collection of objects on the wall, one man had a collection of hats, another had a collection on a table of broken sculptures, and he had his guitars. Once I went inside, I felt it was a much larger place than I had seen from the outside. And then I knew it was physically possible. And it was because they had brought all those elements of home into it, even though it was at a reduced scale, it was all there. That is why it was so important in Fragile Dwellings to show so many interiors.

In the Puerto Rican community [Bushville], their houses looked so much like rural Puerto Rican architecture, they were archetypes of where they had grown up, what they had left, what they had been so anxious to leave to come to New York and yet they recreate this memory almost like something from a Calvino story. This idea of recreating memory in the architecture.

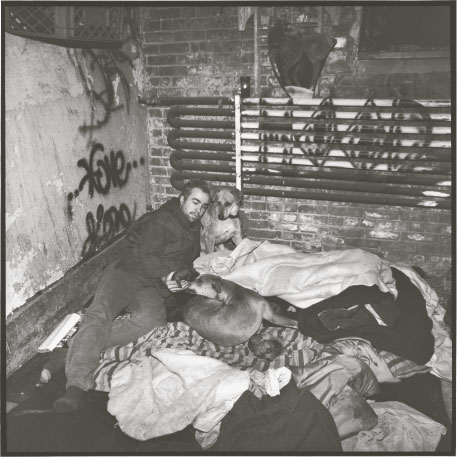

Mark

PD: Books seem to be an ideal vehicle for your projects because they can convey the images and stories in a seamless manner. Do you always see your projects as books?

MM: I do have exhibitions, but I have to say that the book is the art form that is primary to me. I have tried using video but it did not bring things together for me artistically. I do not have any rationale for that. It certainly puts the voice and image together, but there is something very detached about it, in an odd way. I like the fact that with a book you can spend time with it. You can look at the images and find something new each time. You can see all this information in the shadows that in the video you just would not have time to see all that information, which is ironic. In the underground tunnels you would see something very domestic – a cooking pot in the shadows. You would miss all of that in the video. I like to slow things down. I like to look harder and still photography allows me to do that.

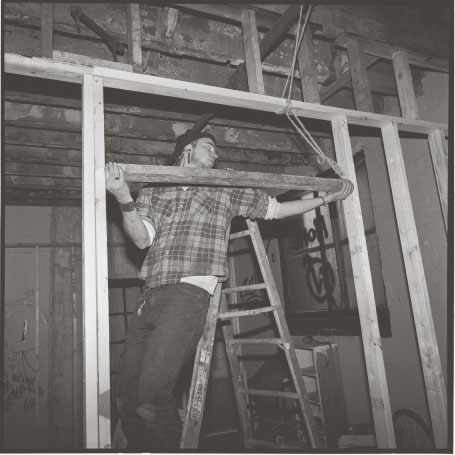

Scott

PD: Do you teach documentary photography?

MM: I teach a class on the photographic narrative. Instead of the defining moment in photography, how you would produce a sequence of images. They do not have to be books. There is a storytelling aspect to that. Some students don’t create stories. They may create a sequence of images, showing things in a multiple way. It would be hard for them to do the kind of projects I do because they are made over several years. I created this class last year. It is about narrative structure and how one works with it in photography. They can deal with fictional situations if they want.

Tobi and Calli

PD: With these last three books you have completed, how do you see your work – your practice – as an artist in society today?

MM: I do not have this preconceived sense of myself as an artist in today’s society and how I am positioning myself. My projects tend to find me out. I had no idea in 1989 that my life would take this course, my work would take this course. It was not a strategy, it just evolved. My curiosity about one thing, took me to another thing. And then after that the people I was photographing created this other energy, and I became caught up in it. I am not a contemporary artist in the sense that I do not have a fixed theoretical idea that I set out to illustrate in some way. I don’t work that way at all. It is a big disappointment when I speak to German artists (amused laughter). I just try and stay open to chance and events and let them take me places that I would not think to go on my own. It is hard to make that point in a contemporary art practice, especially with students, because they are getting this more theoretical approach. I do not disagree with it and I certainly find it interesting and valid. People should certainly be aware of that context.

Personally I don’t ever want to close off these just chance encounters, and events that take me from one place to another. In The Tunnel, for example, a man on the East River told me about the tunnel, told me where to go and what air vent to yell down, and whose name to yell. Someone living on the East River tells you to go to this intersection – this traffic island at 96th street [West Side] on the river and to walk out to the middle of this traffic island with traffic whizzing by and to yell down an airshaft the name of this person who you have never met before and hope he responds. It is not something that comes out of a theoretical construct. Information comes to me and I choose to act on it. I follow my curiosity. I just have to trust that about myself that the project will find me.

PD: Engagement in the larger world, beyond that of the art world, is important to you?

MM: An unexpected aspect of the work, coming from a “studio art school environment,” to end up doing a project that was outside the art world, also in its reception. The Tunnel was published as news, some of it was published as art, and some in architecture magazines. It drew me into this larger world. The exhibit for the Glass House will be at the Urban Center, and the Municipal Arts Society is sponsoring it. I absolutely delight in the crossing of boundaries. Even to do a book that is out in the world, not as a unique artist’s book. I like the way it feels to not be within the narrow construct of what it is to be an artist. I certainly respect that, and I teach in an art school.

It is important for me to know people from different situations. Last week my publisher had the launch event for Glass House, there were people from Glass House there, and there were people from all different levels of New York socio-economic levels in this little room talking to each other and sitting on the same tables. Somebody commented that they had not been to an event like that where there was such a range of people from different backgrounds, but everybody was so comfortable with each other. I had not thought about it, but it is a wonderful thing that my art kind of embraces all of that. And that my life has crossed all of these other lives in some way.

© Copyright Margaret Morton- PradeepDalal 2004

More information is available at:

“Glass House” exhibition runs at The Urban Gallery from December 8, 2004, through January 20, 2005. The Urban Gallery is located at 457 Madison Avenue, between 50th and 51st Streets in New York City.

http://www.mas.org/Events/exhibits.cfm

Bibliography:

Morton, Margaret, Glass House, The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, 2004

Morton, Margaret, Fragile Dwelling: The Homeless Communities of New York City, Aperture, NY, 2000

Morton, Margaret, The Tunnel, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 1995

www.fragiledwelling.com

http://www.psupress.org/GlassHouse

Pradeep Dalal is a writer and photographer living in New York City.